Americans consume 73,000 tons of avocados during one Super Bowl game alone. But Americans are not alone in this global frenzy for avocados with Europe and Asia upping their imports. Outside the U.S., avocados are also all the rage. According to a recent Report (Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030) from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), avocado is expected to become the second-most traded major tropical fruit by 2030, after bananas. France alone, the leading European consumer of avocados imported 182,000 tons in 2020.

See you later, Alligator!

A fruit that previously harbored the unflattering name of “Alligator Pear,” now enjoys the starring role on the world stage of Instagram fueled by vegans and fitness addicts. The theme of avocado is recurrent among different groups but particularly, among young women aged 25 to 34. An exotic fruit bearing the reputation of versatility, avocado can be found in/on sushi, burgers, toast, salads, smoothies in addition to the traditional guacamole dip. How can this global success be explained and what does this sudden passion for the avocado reveal?

The qualities of this exotic fruit (“healthy,” nutritional value, tasty, aesthetic, malleability) are valued and appreciated by the users of social networks and more particularly by the millennials. Whether eaten outside or at home as an assembled finished dish, it owes the globalized reputation to the diverse ways an individual can invent and customize avocado recipes to their own liking. If avocado were a software, it would be “open source”.

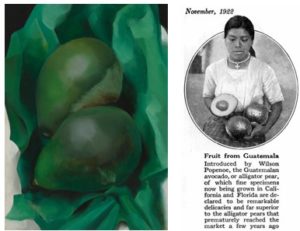

Originated in Mexico and Central America, Avocado trees were first planted in Florida in 1833 and then in California in 1856. In the early 20th-century, they were called “alligator pears.” Their rough olive skin and shape resembled a ‘pear’. American artist Georgia O’Keefe’s 1923 still life painting representing two avocados is titled “Alligator Pears”.

But in the 1920s, the California Avocado Grower’s Exchange launched a petition to ban the term “alligator pear” and renamed the fruit to make it more widely marketable, pushing to get back to its name of origin – the word “avocado” being derived from the Aztec “ahuacacuahatl.”

From homemade cooking to assemblage cuisine

The omnipresence of the avocado consumption aligns with the values of millennials. Well-being, self-acceptance, sharing, and conviviality are the core of their consumption codes, mirrored perfectly in the avocado. Gen Y value natural foods, the predilection for a cuisine preference for individual, customizable dishes, and the aestheticization of culinary practices.

In contrast to the hyper-processed foods, the avocado is emblematic of naturalness akin to the raw food diet which has experienced a boom since its popularization in the 1990’s in California. Its creamy texture and flexible inclusion with both sweet and salty dishes allow many variations; it is no surprise that it’s popular with millennials on the quest of customizable dishes.

Individuation and aesthetization

The avocado is generally eaten in cold dishes where various foods are assembled, thus frequently associated with bread, mushrooms, salmon, shrimps. This is explained in part by the fact that the fruit contains a lot of oil and is therefore complicated to cook. This move away from cooking with fire is typical of millennials who appreciate the varied possibilities that ‘assemblage cuisine’ offers. It allows for creativity and customization. But how did we get to the idea of “assemblage cuisine”?

In the 1960’s, the housewife took charge of all the tasks in the kitchen dedicated to the preparation of meals. Then in the 1970’s, many marked by the acquisition of rights for women took her away from the kitchen, hence the success of ready-made meals synonymous with women’s independence and their social gains. In the mid-1980’s, the calorie-rich “good for you” dishes became fashionable again combining the values of sharing and pleasure. From the 1990’s, the snacking trend spread in increments and led to the de-structuring of meals.

Today, we are witnessing the desire of women to re-implicate themselves in the kitchen without giving up their acquired advantages, especially of time and availability. It is from these parameters that the notion of assemblage cooking was born. But be careful, “assemblage cuisine does not mean impoverished” (Josette Michaud, Maggi’s marketing director), “but it does mean personalization of recipes”. Avocado therefore fits perfectly into this notion of ‘assemblage’.

Majority of dishes consumed with avocado are individual dishes which allow for greater creativity. Each person, according to social models develops his or her own way of life and rhythm of life and aspires to assert their individuality – in particular through food consumption. The consumption of avocado is in line with this trend of individuation of food practices because it responds to a desire to assert one’s identity and values in a more fragmented world.

The avocado-mania by consumers on social networks highlights the importance of the aesthetics of the dishes. Millennials are not just eating avocados; they feel a certain need – even pride – in being able to display the food they are about to eat. With its delicate green color, the avocado has a distinct look that lends itself well to photos. Beyond the agreement between the codes of consumption of avocado and those of the millennials, the aesthetics of the avocado itself seem to govern the consumption among the latter.

Avocado: the “codes” of consumption

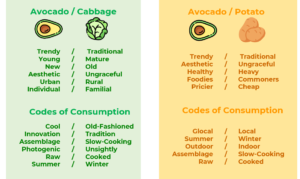

To better understand the main lines of the codes of consumption – and of the symbolism – associated with the avocado, two vegetables considered relatively ‘traditional’ in French cuisine were chosen for comparison: cabbage and potato.

Cabbage has been cultivated in Europe since antiquity, and has long been appreciated for its nutritional qualities, but nowadays is less common in our kitchens and is often neglected by chefs and restaurant owners. In contrast, the potato is native to South America. Like the avocado, it arrived in Spain and Europe with the Conquistadors in the 16th century. Introduced in Western cultures as early as the 17th century, it became a permanent part of the late eighteenth century diet, and a major weapon in the fight against food shortages.

The millennials have constructed the new codes of avocado consumption which are in direct contrast to the cabbage and potato.

The fruit that triggers emotions

If the avocado is present on social networks, it is due in part to trend catalysts such as Vogue and Elle magazines that regularly publish lists of restaurants with the most Instagrammable dishes. Obviously, avocado makes an appearance in these lists. Thus, the aesthetics have become abreast with the quality of the food when it comes to consumer preferences.

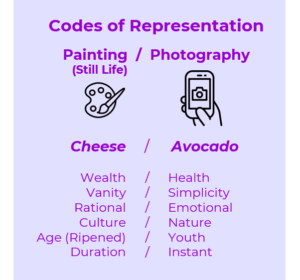

The visual relevance of food is not a new concept although it is more widespread today. In the 17th century, documented food generally symbolized a certain opulence (the presence of fruits, shellfish, fish, ham, olives, nuts, sweets, pies, etc.). The painting of Floris Claesz Van Dyck is symbolic of this taste for opulence. One can observe the importance given to cheese. Indeed, cheese, which can be stored and preserved for many years (especially Dutch cheese), is synonymous with rationality in the use of time and wealth.

Today, the context & priorities have shifted. The avocado is photographed not as a symbol of opulence necessarily, but as a “healthy” product with high nutritional qualities. The consumers are all about a meticulously measured diet in order to stay fit and in shape. Contrary to cheese, the avocado is a consumption of the moment (it ripens very quickly), almost emotional.

The 17th Century still life food present in its apparent disorder suggests the meal in progress aiming for us to enter the intimacy of the setting as guests whereas the photography of the perfectly curated avocado dishes suggests a meal with special attention given to the presentation of the dish that has not yet been consumed (or allowed to be consumed). The intimacy or disorder is generally banished to present a smooth and ‘perfect’ lifestyle: the photo posted on social networks is often the façade of an idealized life to capture attention as quickly as possible. The rythm of temporalities is thus not the same today.

For an entire generation, posting photos on social networks is a way of “eating alone together” and almost a replacement of a direct social link. As Eve Turow-Paul wrote: “Posting images of our dinners on social media both fulfills and feeds our hunger for human connection in an increasingly isolated world” (Hungry, BenBella Books, 2020). It has become an unavoidable practice that meets the need to belong (to a group, community) but also to the need for esteem (recognition and appreciation of others, trust, self-confidence, and self-respect) of the human being. The avocado is a vessel for this new palette of emotions.

Avocado – “I do … but maybe not”

If the millennials had an iconic food of their own, it would be an avocado. Its significance goes beyond being an object of consumption or aesthetical admiration. When Coca Cola launched its avocado flavor, it immediately identified this new taste with millennials and Instagram. Brands are indeed banking on the fashion effect around the avocado contributing to their promotion on social networks.

The avocado mania is proliferated via merchandising: mugs and t-shirts with humorous slogans (“Avoca-do it”, “Avo-cardio”), which correspond to the values of millennials. However, this appearance of the avocado as a motif on consumer items also highlights the dangers and the drifts of a globalized food.

It begs the question: is the buzz around the avocado doomed to disappear? It is largely due to social media that the avocado has managed to become a star in the world’s kitchens. However, if food trends are born and grow via photos shared by Internet users, there comes a time when consumers become aware – again via social media – of certain issues related to the consumption of their favorite food fetish. The fall is thus precipitated by the social networks themselves where the craze started. That said, once one food fad disappears, another one is ready to emerge.

That is why the avocado phenomenon is likely to shift to another food just as the fad had moved from quinoa to avocado. The journalist Joanna Blythman wrote two articles in The Guardian three years apart: one on quinoa consumption (2013) and the other on avocado consumption (2016). She denounces the environmental (deforestation, water shortage) and social (undermining of indigenous cultures) consequences of the cultivation of these two commodities and questions the reaction of their main consumers (vegans and hipsters respectively). She even goes so far as to accuse Western countries of an avocado fetish at the expense and detriment of the local communities where the fruit grows. Once referred to as “green gold” avocados are now compared to blood diamonds and commonly referred to as “blood avocados”.

In Mexico, the world’s largest avocado producing country, the avocado industry represents billion dollars in profits per year and sales have increased 30-fold in just 15 years. Mexican cartels have no intention of missing out on this flourishing market and are profiting greatly from this growth. Regularly, avocado growers are extorted or murdered (hence the expression ‘blood avocados’) and deforestation is constantly on the rise.

On social networks, negative posts about avocados have increased sharply between 2016 and 2018, according to Linkfluence. This turnaround is explained by the awareness of consumers of the ethical and environmental issues associated with their production. Hence, the rise of new hashtags such as: #boycottavocados on Twitter or #byebyeavocado on Instagram.

Faced with this consumer awareness, some restaurants are making the choice to remove avocado based dishes from their menus. At the end of 2018, the United Kingdom experienced a small wave of avocado abandonment by committed restaurateurs concerned about their social and environmental impact. This is the case of Michelin-starred Chef JP McMahon (Ireland) who abandoned the avocado for a myriad of local options (British and Irish) such as kale.

At the beginning of 2020, the Café Marlette (Paris) crossed out avocado from their menu. They proudly announced it on Instagram, explaining that the decision was in line with their values. Parisian Vegan restaurant Wholywood, announced that it was thinking about an alternative to avocado: a guacamole made with broccoli-based guacamole (“brocamole”) to remove avocado from its menu.

The ‘codes of consumption’ as defined and displayed by avocado lovers bring to light several key points. First, the avocado consumption is in “consonance” with the millennials expectations – in short, naturalness as well as the preference for individuation and personalized meals. These consumption codes are aligned with the rise of “assemblage cuisine”.

These ‘new codes’ as identified in contrast with cabbage/potato allow us to understand the presentation and the representation of the avocado dishes – the millennials using social networks to send back embellished images of their lives where the need for social recognition and acceptance thrive. The age of digital expressionism!

Contrary to Still life which remind the viewer of its finitude and the passage of time, the photographic representation of time of our culinary practices is anchored in the present, the immediacy of the moment. If the fashion around the avocado seems to leave place to the criticisms of production today, this does not mean that the Instagramming of our culinary practices is doomed to disappear.

On the contrary, it will take off again as soon as a new star has been designated. But what will be the food that will succeed the avocado? Will it be an exotic product again or will the eco-activists push us towards a more local alternative like broccoli? To be continued (on Instagram!) . . .