I have long been fascinated with the cheeses of Anatolia, even before I became aware of all the historical connections. But with one of them, I really fell in love. The object of my desire is a rather curious fellow, a sheep’s cheese in a hairy goatskin, called Divle Tulum. When I met ‘him’, I had no idea of how large a family Turkish tulum cheeses are; the curdled, drained, and salted milk pressed into animal skins, a testimony to nomadic herders’ pragmatic approach to transport and store, a migrant way of life practiced for several Millennia.

The first taste

I first met Divle Tulum in Istanbul, that great, crazy city on the Bosporus which always reminds me a bit of India – almost anything is possible. On one of my first visits, a colleague of mine, a well-connected food expert and columnist, took me to the spice bazaar and the delicatessen Cankurtaran Gıda, where the sky is indeed full of sausages and honeycombs – and Turkey’s best cheeses.

One by one, I had to taste them, including some rather acidic chunks: “Tulum”, I learnt, “means tube or sack, and refers to one of the most traditional types of cheeses in Anatolia: drained, salted curd matures in cleaned animal skins sewn together to form a tube.” Unusual, a little salty, but full of character. “This one comes from Erzincan, in eastern Anatolia, near Elazığ.”

I had been to Elazığ on a previous trip, to check out my favourite Turkish red grape variety, Öküzgözü, and I could well imagine it with this cheese. But the best tulum, I heard, came from Divle, about a hundred kilometers inland from the south coast towards Konya, the city of the dancing dervishes, and it was quite different from the Erzincan one and ripened in caves. However, it was difficult to find at that time of year…

But that meant underestimating Istanbul. Before long, I was sitting in front of a large cheese platter with the two owners of another Istanbul delicatessen, Antregourmet. There was yet another Tulum, from Kargı on the other side of Anatolia towards the Black Sea. It seemed livelier and more playful in its acidity, full of concentrated sheep’s milk sweetness as a counterpoint, the white fur shorn short on the outside but similarly soft and cuddly as its contents. “It’s from this year,” the two explained to me. And then, indeed: tulum from Divle!

Again, very, very different. A firm, but not hard, mature cheese that reminded me of Jamie Montgomery’s cheddar from Somerset in texture, very flaky. Clearly this cheese was over a year old, there were notes that reminded me of brown butter and caramelized garlic, lingering…. They showed me pictures of the cave, with white, blue and orange-red fluffy mold growing on the skins, so beautiful! That’s when I was truly blown away.

Meeting the Cheese Caretakers

“Sleeping milk” is what the 11th-century Turkish scholar Mahmûd Kaşgarlı called cheese; milk that has found a longer lasting form, nourishing, and strengthening even when the animals are not giving milk. The “putting to sleep” is often surrounded by rituals that also strengthen social connections. Sometimes it is forgotten why something must be done in precisely that way, but in Anatolia I met several women who are very aware of the connection between past, present and future. They do not want to give up everything for the sake of modernity, and some revive what has been almost forgotten. When I finally made my way towards Divle, our first stop was to meet a woman who acts as the caretaker of Bastırık, the “wrapped” cheese.

This time, a mother and daughter team were my guides whose online shop featured grains, spices, dried fruits and nuts in addition to cheese. Together we drove to a village near Karaman, two and a half hours southeast of Konya, past fields of maize, melons and sunflowers. We had just caught the short window in mid-July when the chickpeas are ripe, everywhere along the roadside were small trucks with the fresh green branches, and women sitting next to them in the shade busy husking them.

The story of the Bastırık

The saviour of the Bastırık introduced herself as Niğda Ay, a stocky, humorously vivacious woman in her mid-fifties in culottes, a red jumper and a scarf loosely draped around her head. She led us into the courtyard of a modern building, next to which sheep bleated while neighbors kept cows. She told us that they had moved there 17 years ago, from a farm without any running water or electricity – and still she’d preferred it. She offered us fragrant apricots, showed us sugar beet leaves for dolma, sacks of maize, beans, wheat, and barley that they still grew, and the brick oven in one corner.

The bastırık was hidden under a large upturned wicker basket to protect it from cheese-eating animals – earlier on in the village they used to store it on the roof. Under the basket were first carpets, then blankets, curtains and shawls, and finally all kinds of (winter) jackets, skirts and jumpers. Amidst much laughter, the women took it all off, and even on that hot day the layers became cooler and cooler, until finally the black fur of the Bastırık appeared, sitting in front of us like a chubby little child.

The Bastırık is a large tulum in the skin of a young goat, its openings carefully sewn shut except for the neck. Niğda Ay showed us how, after pressing and crumbling the curd several times in a cloth bag, she filled it into the skin through the neck with the help of a funnel and a wooden stick and scrupulously stuffed it tightly to avoid it going moldy. Then the skin must be pierced to allow the cheese to breathe. Bitter water will leak out, which is why it had to be washed once a week, like a baby, she laughed. After evening prayers just before sunset, the cheese needs to be unpacked – traditionally by the youngest married woman in the house – so that the night air can blow around it before it is time to pack it up again in the early morning.

The many layers protect it from the heat of the day, the same principle, but applied in reverse, as with cooking boxes, in which hot food continues to cook without further heat input. In the past, butter and yoghurt were also cooled in this way (and beer, her husband smiled). The Bastırık needs to mature for 45 to 90 days, depending on the size, humidity and temperature, and its taste gets better and better, like a wine, both husband and wife agreed. It is eaten as a kind of condiment that goes with pita bread and tea, scrambled eggs, kebabs, in fact with every meal. Traditionally, it was made from a mixture of sheep’s and goat’s milk, but for some years now there hadn’t been enough sheep’s milk because so many farmers had moved from the village to the city.

Divle Day!

In the evening we drove up to Sertavul in the Taurus Mountains which separate the Anatolian highlands from the Mediterranean basin. At almost 1800 meters, nomadic Yörük, up to this day live with their sheep and goats in very improvised-looking summer settlements, and at stalls along the road, yoghurt was for sale. The next morning, a huge breakfast table full of salads, honey, eggs, bread, butter, yoghurt, cheese of all kinds awaited me – though that day, of all days, all I needed was tea: Divle day!

Access to the cave was strictly regulated to comply with the official protection of origin, which was urgently needed for marketing reasons, which in turn was why we first had to go through some official palaver involving a lot of tea. But then we were finally driving for half  an hour eastward, through the barren landscape of the high plateau, which at an altitude of over thousand meters looked like the Wild West in a Hollywood film, rough and inhospitable.

an hour eastward, through the barren landscape of the high plateau, which at an altitude of over thousand meters looked like the Wild West in a Hollywood film, rough and inhospitable.

Eventually, the stony desert yellow-grey gave way to a hint of green-blue garrigue, and the idea of sheep began to make sense – we were approaching the Mediterranean. Rocks eroded by prehistoric floods rose, harboring entire cave systems similar to those in neighboring Cappadocia, used as shelters by many generations of people.. Divle, which is more commonly known as Üçharman, is a small village on a slope towards a small river. Apricots were spread out to dry on one of the red tiled roofs, maize and barley, animal feed, grew below.

The remnants of nomadic customs

We were invited for coffee by a family, and gradually I started to understand, not only my new cheese friend’s background, but also how precarious its current situation was. Everything seemed to be stuck between the past and present. Traditionally, the women milked the white-furred Karaman sheep by hand once a day and processed the milk, guided by their mothers, while the men looked after the animals, typically between fifty and a hundred per family. But even here the sheep were being displaced by cows, of which fifteen were enough.

There were a few new buildings in the village: the cow sheds. The sheep were housed in old ones and referred to by the villagers with disdain in their voices. Right then, in the middle of the summer, the milk was very fat, too fat for cheese, they said, and in general cheese made from cow’s milk was lighter and that was better and “cows make much less work than sheep”. Authentic Divle tulum, however, the mother and daughter team immediately emphasized, must be made from a mixture of Karaman sheep’s milk with a little goat’s milk.

The conundrum was (and is) that prices and demand for genuine Divle Tulum aren’t there yet, to support the hard work of the sheep herders, farmers, and cheesemakers. There were around twenty cheese producers in Divle itself, but many cheeses now came from further afield; in the last fifteen years, the sheep population had been reduced to almost a tenth. Two larger producers dominated the market, along with many small ones producing for their own consumption, and most of the cow’s milk went to the dairy – cheesemaking skills threatened to disappear.

And they still do. These are the last remnants of nomadic customs that have survived for millennia. In winter, the animals were taken down to the warmer Mediterranean basin, stopping in Divle in the spring, and the summer was spent on the cooler plateau, so they passed through Divle again in the autumn. In March, after lambing, the animals gradually began to be milked again, first to make yoghurt (preserved by smoking and traditionally also stored in the cave, although modern regulations would like to put a stop to this) and then to make cheese for three weeks in the last days of May, in early June.

Collect your Cheeses!

I asked the women how tulum was made. After some discussion they said their mothers used to make their own rennet and “the cheeses tasted different back then”. After an hour of stirring, the whey would turn a yellowish white, and the curd was drained (and the whey heated for ricotta-like lor). The next day, they sliced the curd, washed, and pressed it with stones.

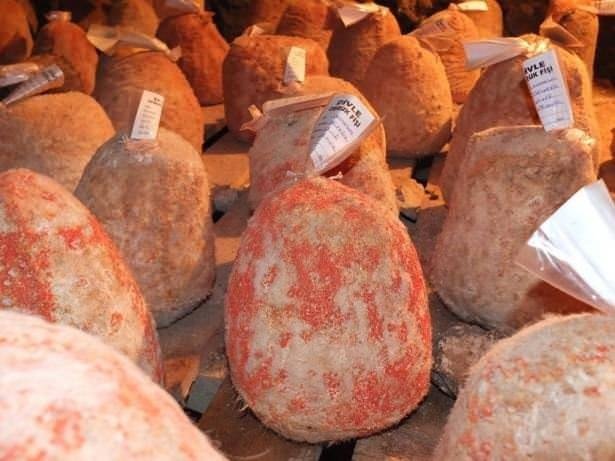

Again, a day later, two per cent salt were kneaded into it, crumbling it up in the process, and these crumbs had to be stuffed very carefully into the leather skins, first for large tulums weighing about five kilos (the best quality), then smaller ones. Again, the skins were pierced and for three to four days had to be cleaned daily before they were finally marked and taken to the cave at the end of June. Access to the cave was controlled by the village administrator, and it is only on 29 October – traditionally a festival day – that everyone was free to collect their cheeses.

The cave! Around the house stood trees loaden with mulberries and plump yellow cherries, and we were urged to pick, to eat – but I wanted to get to the cave, the obruk, now! Finally, we set off again. We climbed over rocks in a marble quarry down to the entrance hatch, because although there was a very simple, blue-painted lift with a kind of lattice cage, it seemed out of use. And then we were standing in front of the hatch – and a big, sturdy padlock.

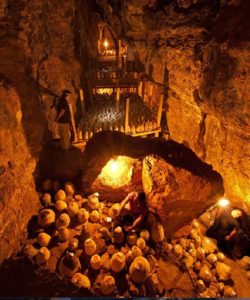

Someone went in search of the village administrator, who supposedly had the key but was apparently difficult to find. I tried to keep my Prussian determination and personal impatience in check. So close to the goal… secretly I examined the stability of the metal lid, maybe one could?! But then the cheese gods had a change of heart, a little boy came running, nimble as a mountain goat he waved the key from afar. A long, rusty ladder lead deep down. The lift started up after all, not for us, but for the village administrator. I carefully descended into the thirty-meter shaft. It got darker, more humid and really cool; I didn’t have a thermometer, but they said the temperature was a constant four degrees Celsius.

The Big Reveal

And then: Divle Tulum. Everywhere, in all sizes, shapes, colours. It was a hard-to-describe, surreal moment. To have finally made it to this source, to breathe in the cave air, fresh and yet homely like in the cave hotel where I once stayed in Cappadocia, but also with a heavy spiciness that is due to the cheese. The long passages were stony, damp, and slippery in places, and there were wooden footbridges and ladders to climb, and I was glad of my sturdy shoes, especially as I could hardly take my eyes off the tulums.

Officially, the cave held thirty tons, but there was probably twice that amount. Along the passages, on ledges, in niches and on wooden shelves: tulums everywhere. Illuminated by scattered bulbs and the light of our torches, some curly like teddy bears, white-haired, black-haired, others almost bald, some like a handbag, others you wanted to hold like a baby, pinned shut with wooden skewers, tied with string, sealed with plastic clips, with a label or without, but all in the characteristic bag-like shape.

I’m not sure how much time I spent down there in the cave, time seemed to have stopped, in retrospect as blurry as the shaky pictures on my smartphone. When the village administrator took us one by one up back to daylight in the lift, I felt like in some kind of dream for a long time. When I could think reasonably clearly again – even when travelling through time, the soul needs much longer than the physical body – I tried to sort out the new impressions.

What makes a tulum a Divle Tulum? There were, after all, other caves like this that were also used for cheese storage – though I was told that only this one holds these very specific cultures. What distinguishes Divle Tulum from other tulum cheeses is its very special, flaky structure. It is not a soft but a semi-hard cheese, reminiscent of the best cheddars from Somerset, and the acidity plays a very confident supporting role in the background, like a plucked double bass in jazz, structuring the sheep’s milk immense richness.

How I would have loved to have a cheese drill down there! The temperature in the Divle cave may be stable, but all the nooks and crannies make for different conditions (just as barrels of the same fermenting must in the same cellar make for different wines), plus the cheeses bring their own stories from the pastures, farms and dairies down below, and therefore react quite differently: on some a thick fluffy white-blue-grey mold grew, on others the rust-red particularly typical of Divle – and all of that influences the ripening of the cheeses inside, the development of texture and aromas. I am sure: Just like us today, the shepherds in historical times were also excited every time they descended into the cave in autumn…

Finally, we were back at the car, and I took a photo of the road sign as proof: “Divle Obruğu”. Mission accomplished. The landscape now seemed even more inhospitable and merciless in its vastness, and I got a fleeting inkling of what a wonderful refuge the caves must have seemed to the shepherds. They were migrants who followed their animals, because they knew that was the only way they themselves as human animals could survive: together with these ruminant ones. That’s the story every single real tulum reveals, and what the cheese gods are trying to remind us of, if only we listened.